How can an inert object produce deeply unsuspecting, indecipherable, uncontrollable emotions? Wayne Fischer is an artist who can create works that force one to ask such moving questions as this. If he doesn’t know why, if he can’t explain the deepest reasons of his artistic research, he definitely knows the workings and limitations of the artistic process he invented.

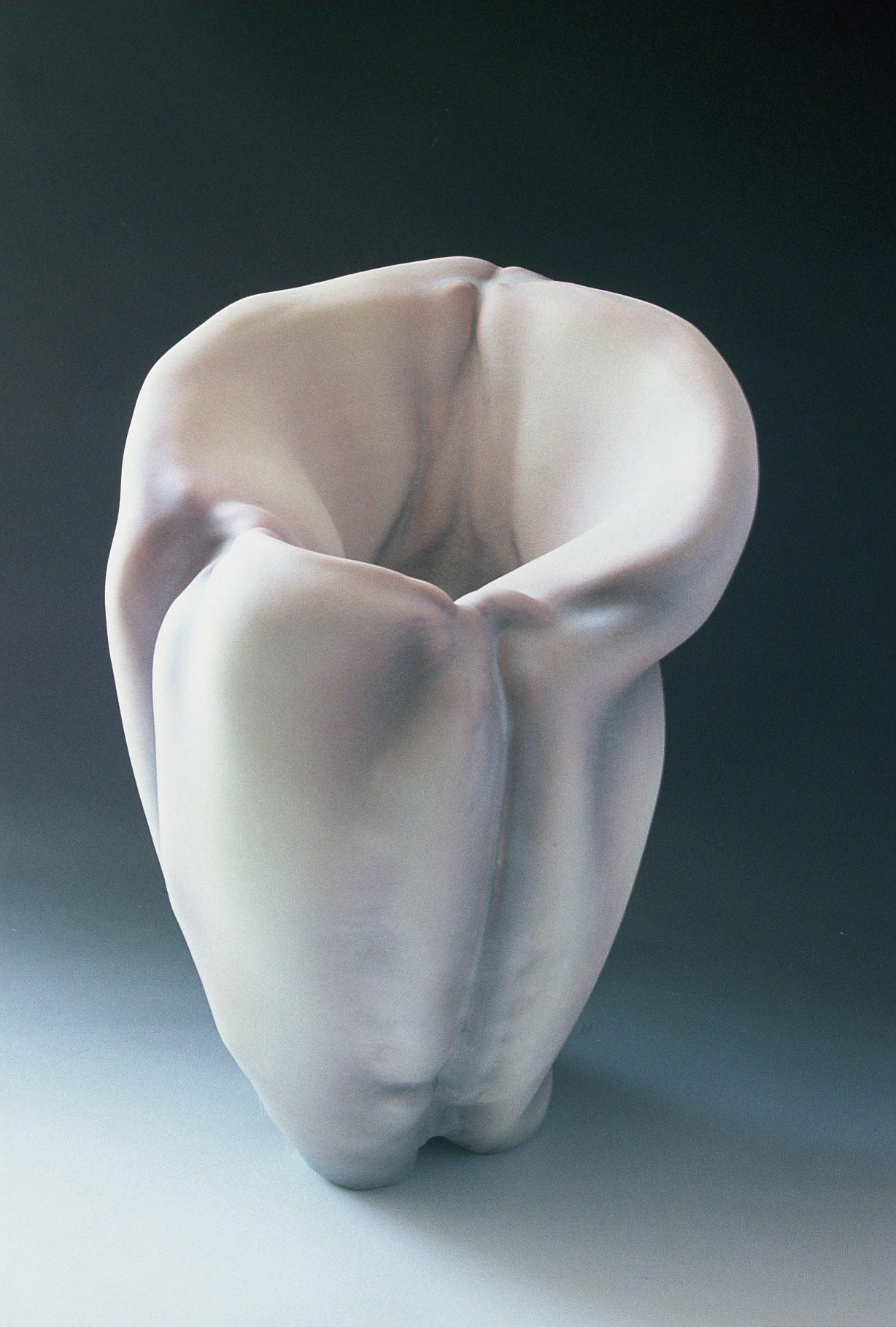

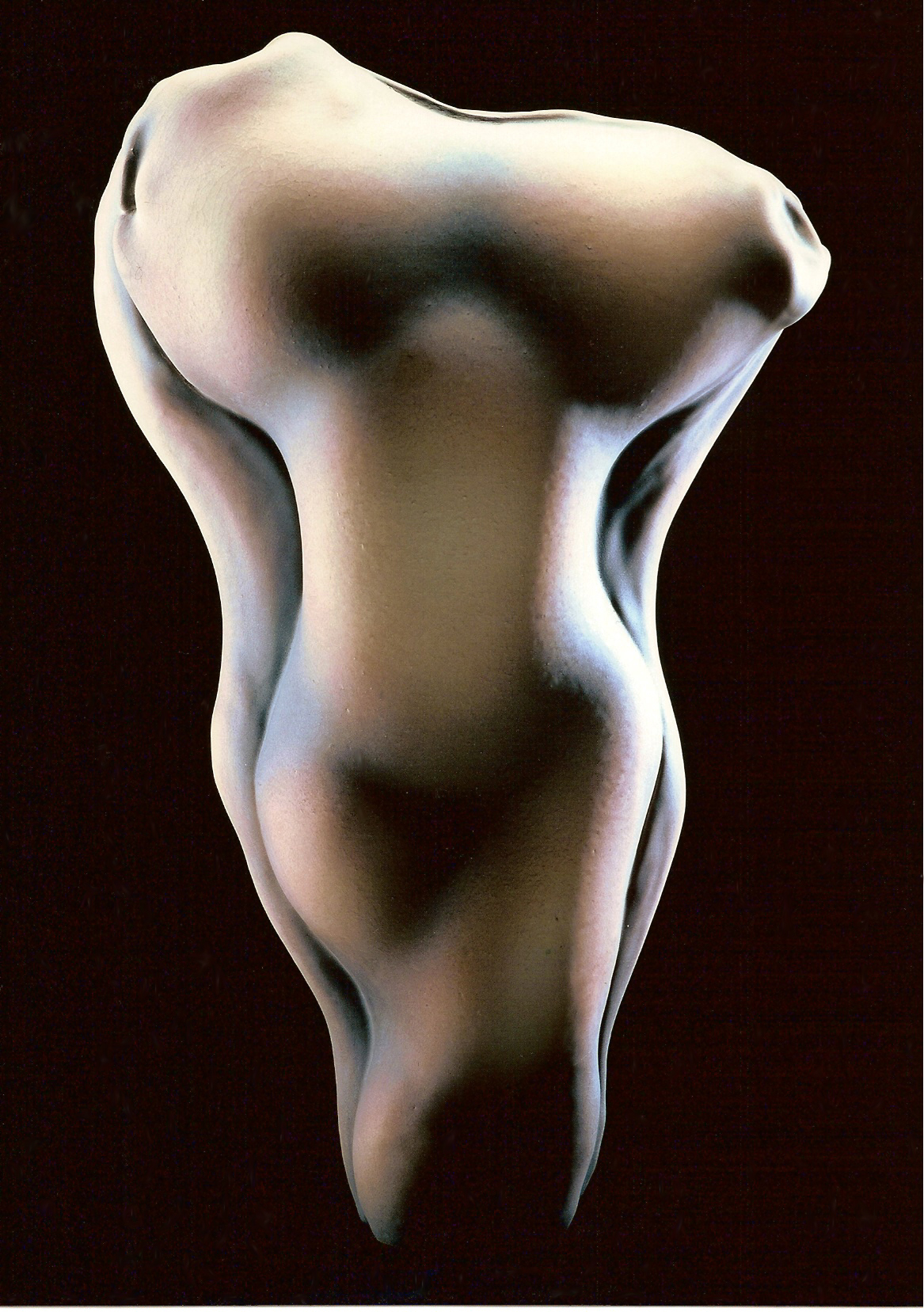

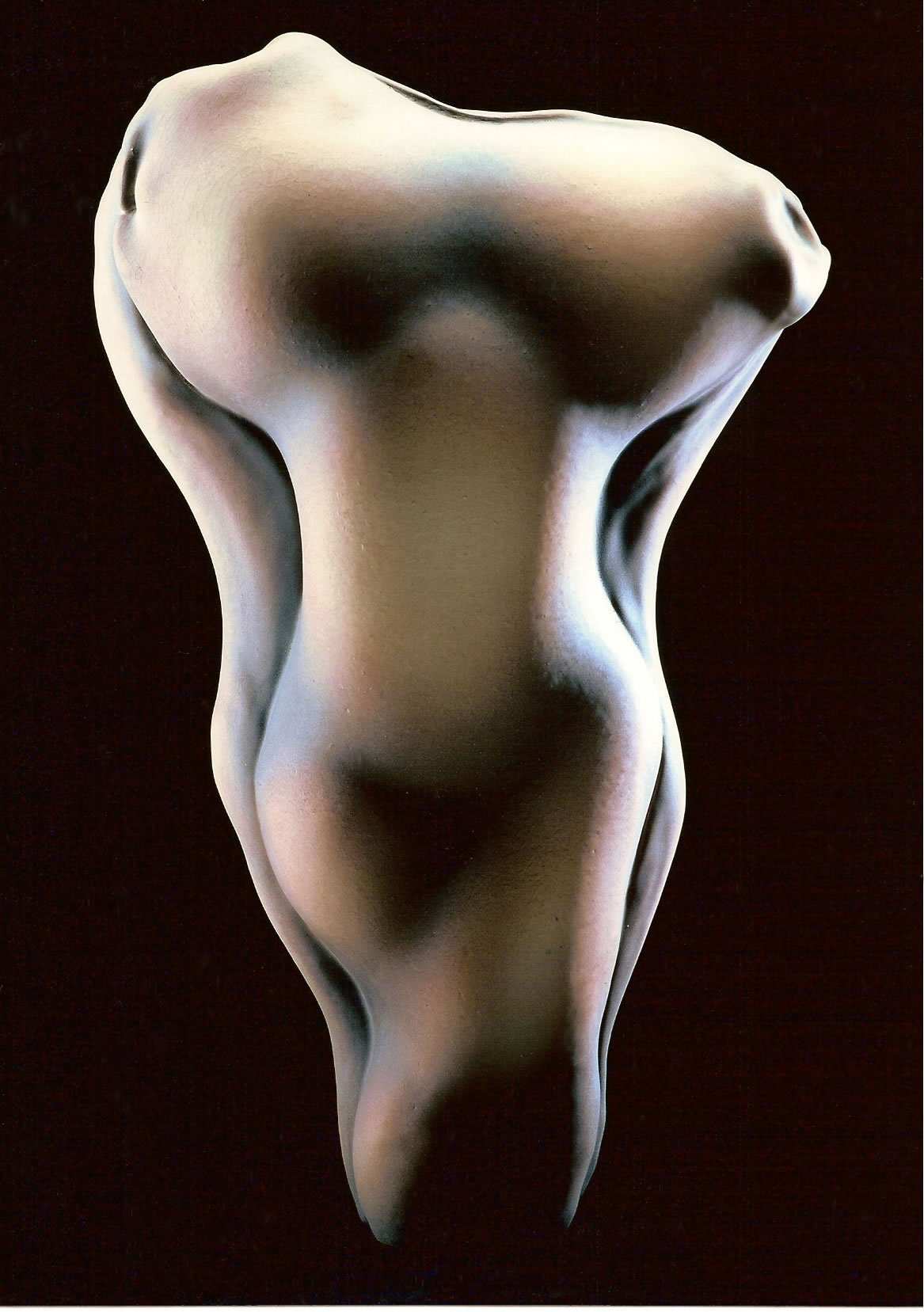

He has never deviated from the course he set for himself since university; translate life. The works presented here show the evolution of his creations over the past thirty years. If Wayne Fischer has received several international prizes and quickly obtained the recognition of his peers in ceramics, nevertheless he retains a singular position at once unavoidable and disturbing. His sculptures are paradoxical, powerful and sensual, and cause a certain unease. They are beautiful, carnal, touchable, all the while being outside the standard idea of beauty. The ambiguity of attraction and rejection is at the heart of this evolution.

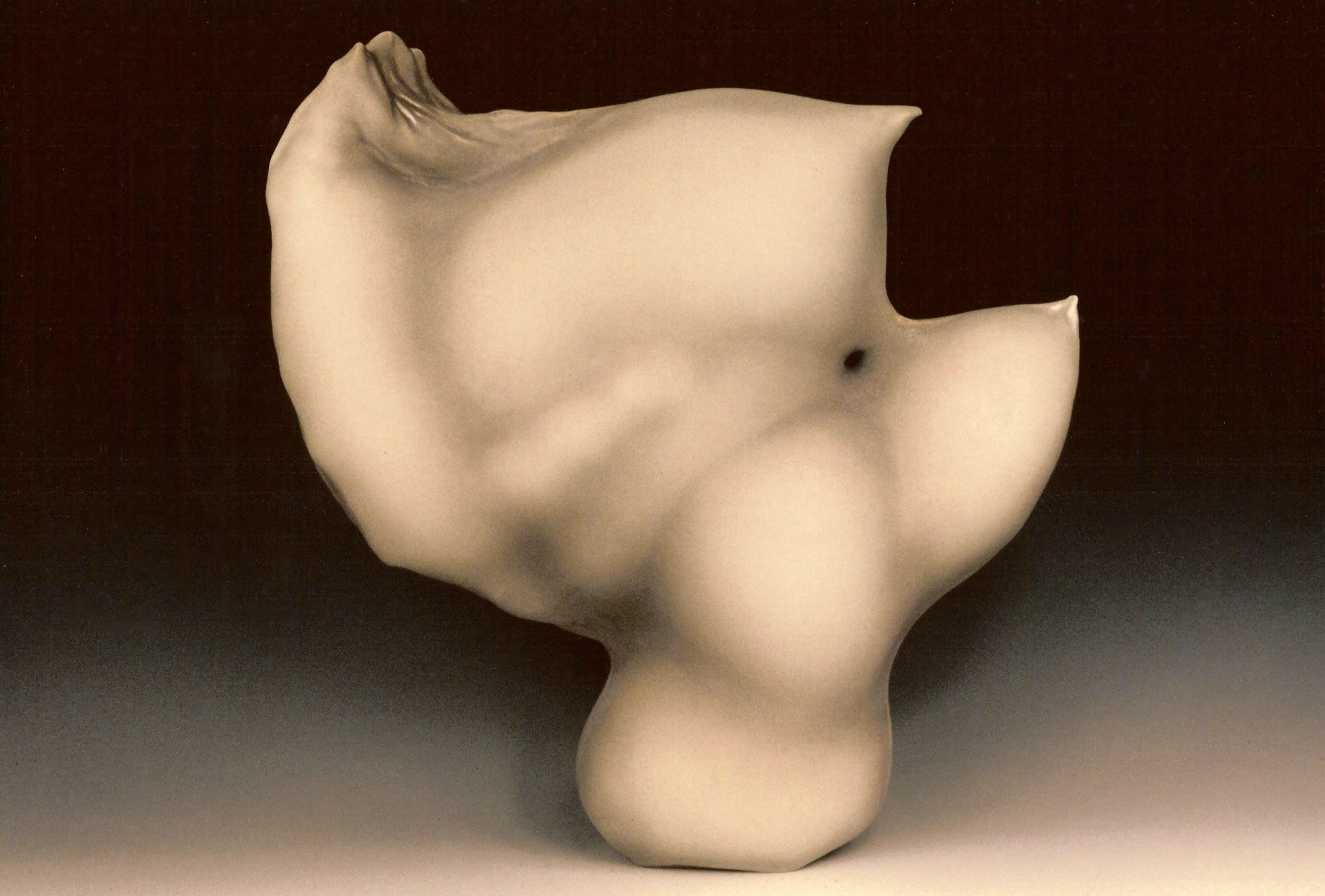

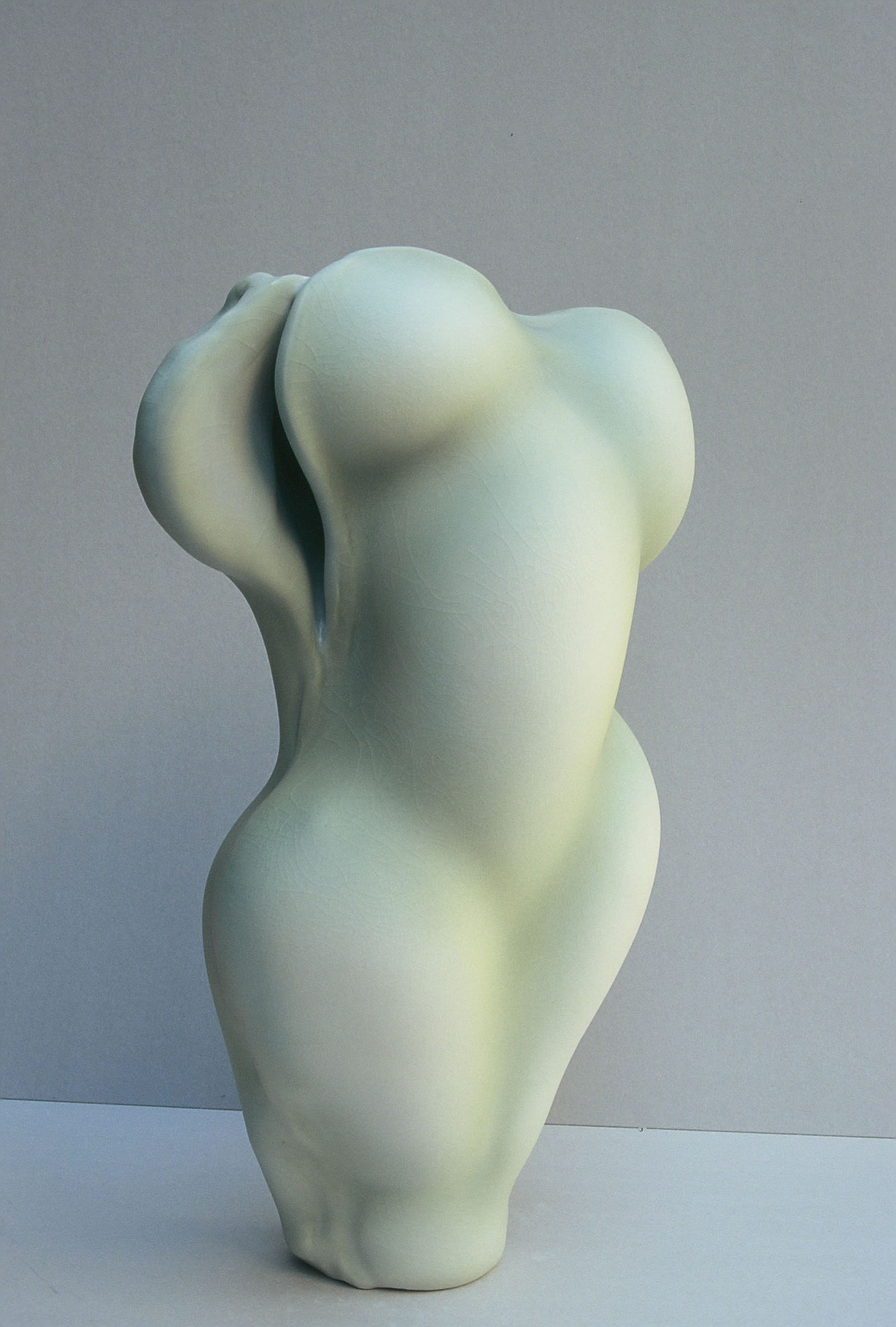

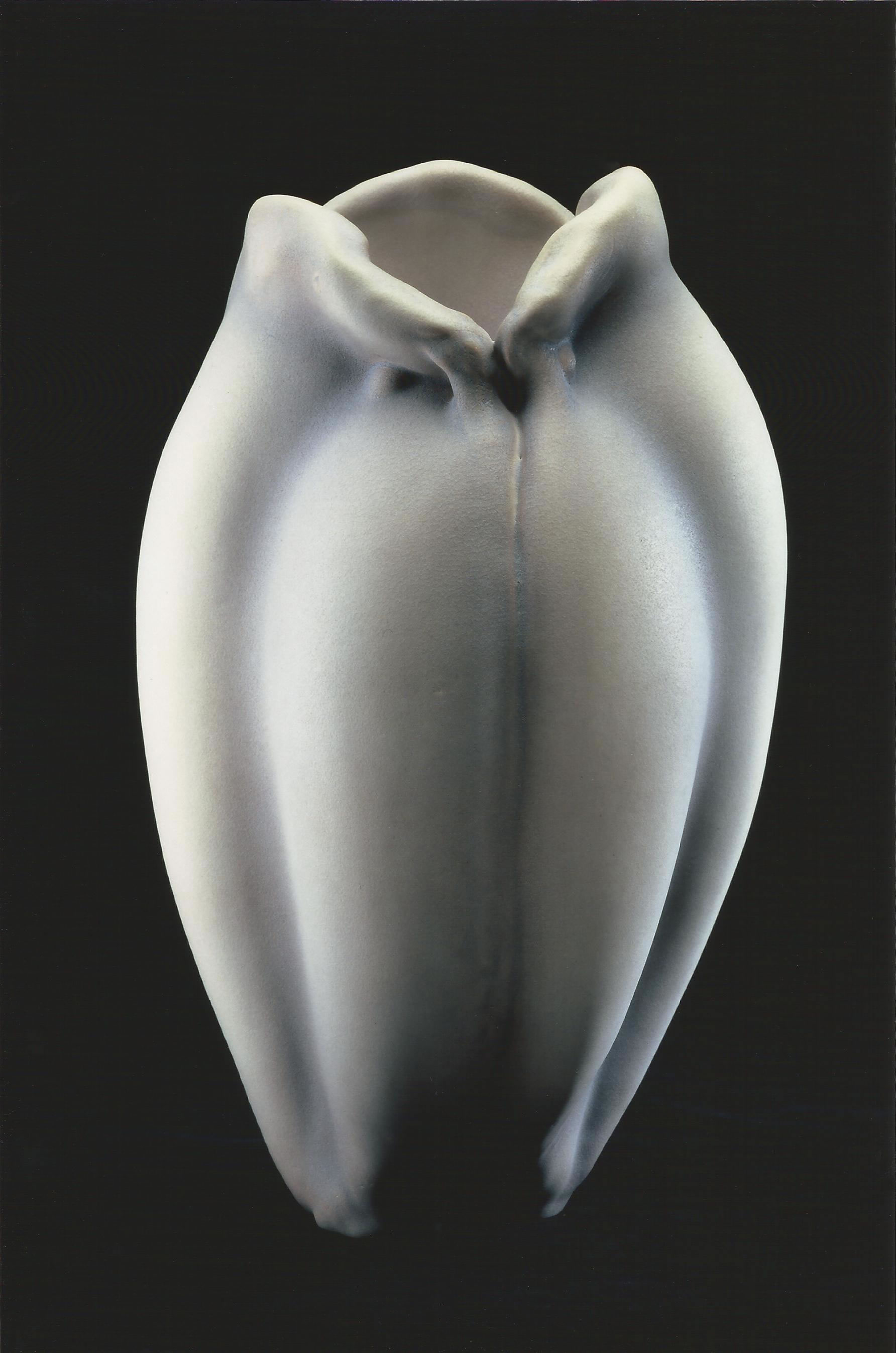

The pieces from the 1980s and 90s are imposing by their size, stature and symmetry, which give them balance. They generate surprise, curiosity and play between contrasts that are both soft and aggressive. They reference the body, muscles, and torso, without presenting an exact reality. They are double-faced, seductive, and enigmatic. Wayne’s shapes are inspired by shells, bivalves, sometimes presented as though they are floating in space. But the reference of the marine world to the mysterious female body has only one interpretation and only history and emotion condition the reaction of the spectator: he accepts or refuses to see, to be seduced. He is touched or he flees.

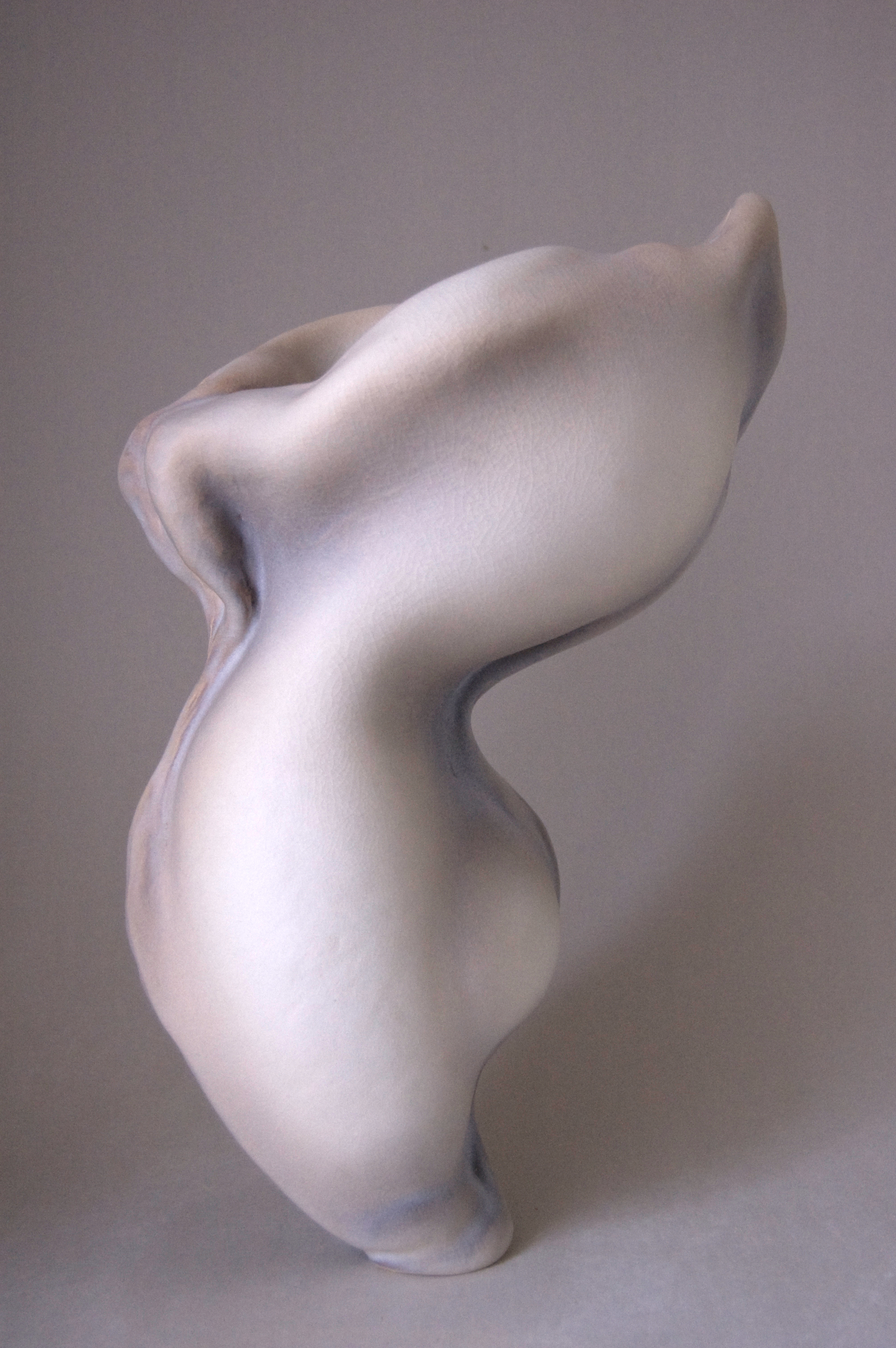

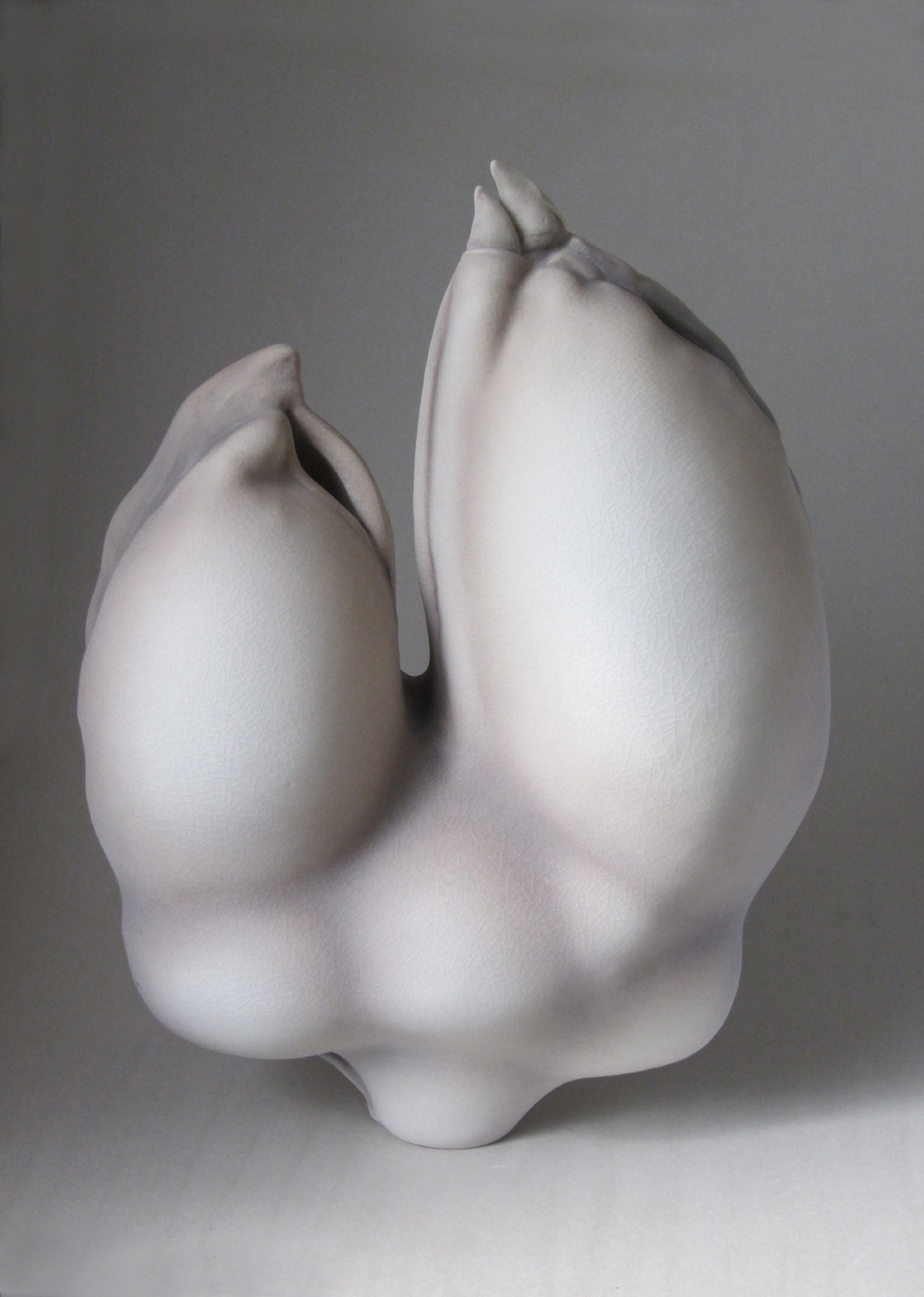

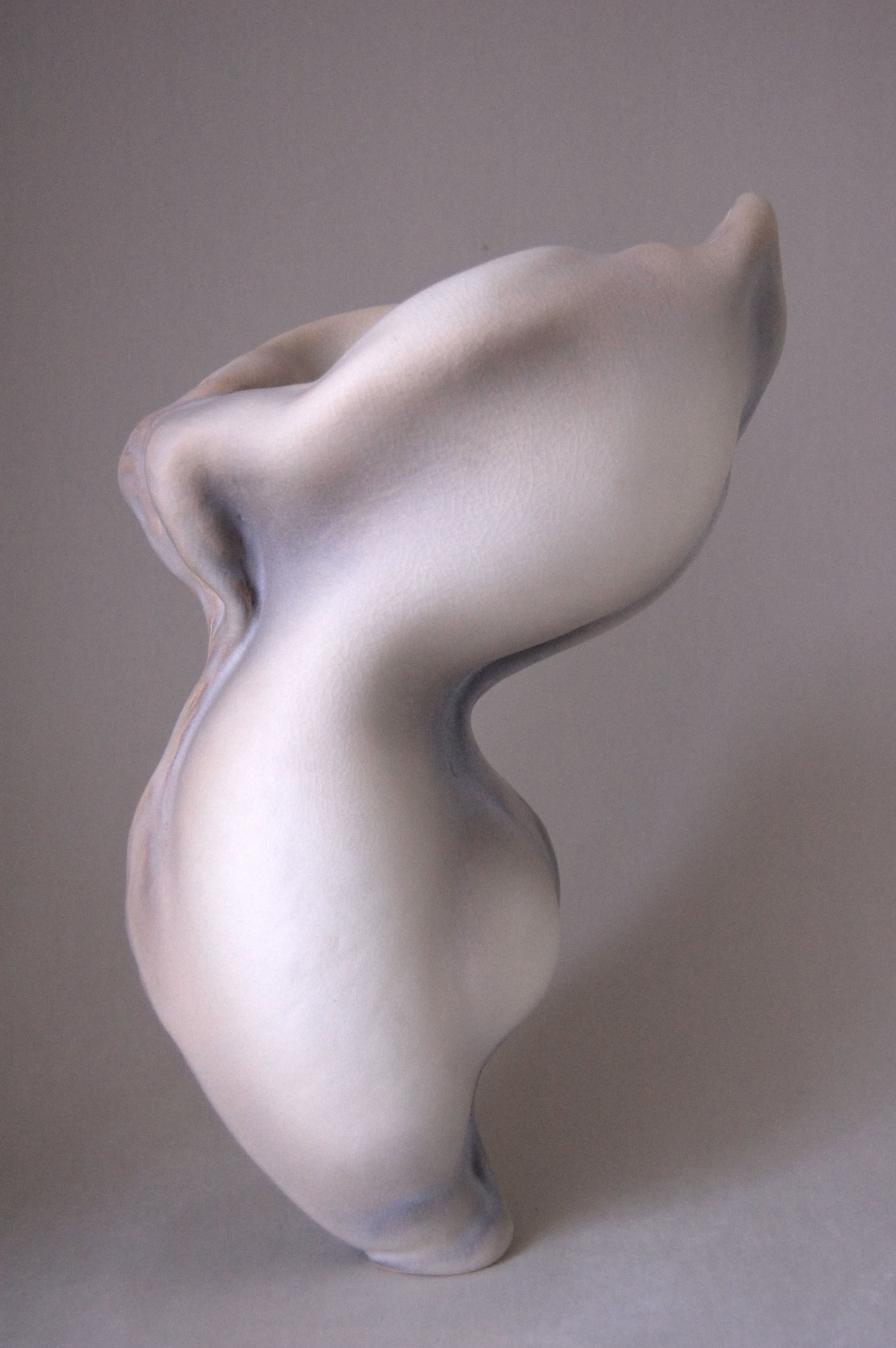

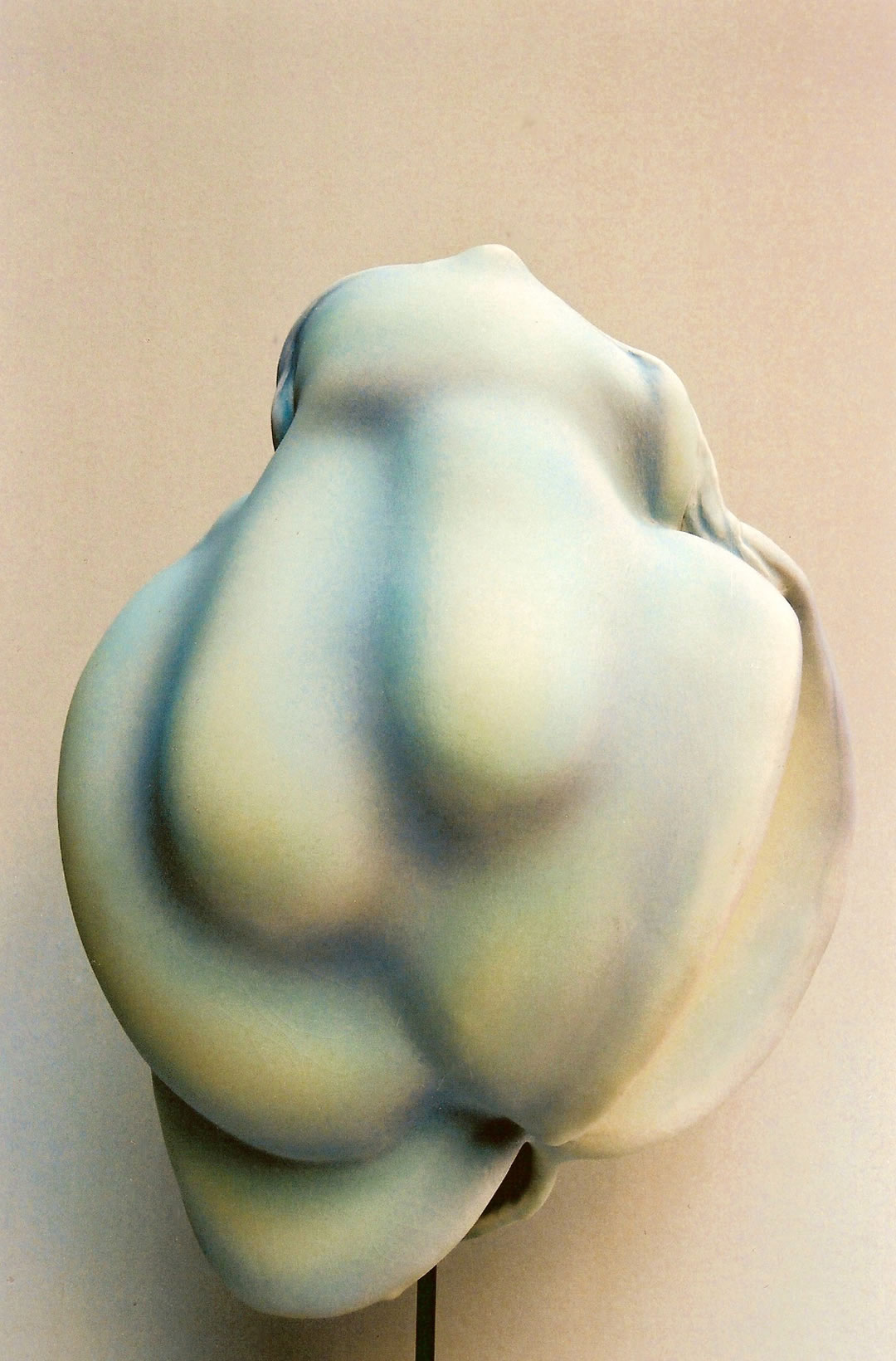

The more recent sculptures are appreciated in the fullness of their round volume and the search for a pure universal beauty. “Metamorphosis,” the work recently awarded by the Bettencourt Foundation, is from this series of pieces wheel-thrown and deformed which pushes the porcelain from the inside so the bulges evoke the movement of waves or the musculature of several bodies. The exactness, the clean breaks, the assurance of lines and valleys are testimony to the interior power that governs the creation. The life energy expressed is also felt by the artist as the origin of ceramics. All the pieces are curved and tense. They show no marking, no sign of the hand, no imprints, and yet give an impression of spontaneity, as if a dropped piece of clay found its form by chance. Depending on the angles, the content becomes “the origins of the world”. Femininity and sensuality are exalted. Inspired by the body, before and after birth, or simply the sea, the parts of the sculpture conjugate around a mysterious interior cavity, secret and troubling. The interior wall doesn’t correspond to the exterior, and has its own volumes, deformities, and intimacy. The pieces present two kinds of interior: one open, and partially uncovered, the other totally hidden inside. The differences of their respective deformation reinforce the impression of life : the subjective representation of muscles and bones, of bulges pushed by an interior force, like a visceral movement of respiration. The surface of the ceramic is crackled but soft and fine, even reflecting light like the skin. The nuances of color reinforce the expression of sensuality.

Wayne Fischer perfected his technique in the 1970s and has remained faithful to it. He adds fibers to porcelain clay that has been chosen for its whiteness to create and accentuate volume around empty space, by assembling slabs or thrown pieces. Then, he makes another pièce that takes its place inside; both parts are formed with no hand mark before or after their assembly. These sculptures are called double-walled. The colorants are airbrushed on, then sprayed with a layer of transparent glaze. The piece is colored in the manner of a painter in mastering the light. The darker parts accentuate shadow and depth, the paler parts come forward and focus on the light. After firing at 1250° Celsius each pièce is sandblasted to remove the shine but leave the transparency, a soft crackling, and an optical fusion of depth. This description doesn't take into consideration the complexity and necessary mastery of this difficult process and perhaps explains why this fastidious technique has not been taken up by other ceramicists. It demands a unique knowledge that Wayne Fischer claims with determination. "You have to feel the material in order to create powerful pieces," he says. A perfect knowledge of materials is necessary for expressing what you wish, but it is equally important to have something to say with this technique.

Wayne is an artist above all. From the minute he wakes up, no matter what he is doing, Wayne is an artist to the point of being disconnected from reality at times. He makes no concessions in his process, nor in the time he dedicates to work. He didn't look for a well-paying job, he didn't give up his art despite suffering and sacrifice, or tensions caused by his intransigent attitude. His perseverance and obstinacy have kept his sculpture at the highest level of quality.

Outside of contemporary artistic trends, without belonging to any movement, without reference to 20th century sculpture, which has favored other materials and techniques, Wayne Fischer innovates. His style is his alone. It speaks of the body without being figurative, but is not really abstract because the pieces exude eroticism. In keeping with simplicity of form (influenced during his studies by the work of Barbara Hepworth) Wayne Fischer addresses the unconscious and seeks to create discord which he himself feels in relation to the works of Bacon, Goya, and Magdalena Abakanowicz. He shows, as does Bernard Dejonghe, that the artist isn't in opposition to the craftsman, that ceramics can give birth to works of art and "bring about thought and emotion and share a view on the world."

Nicole Crestou, doctor of Arts and Art Sciences.